It tasked me. For many years…it tasked me. I’d walk through downtown Chicago with the unwelcome knowledge that something was wrong.

Always one to prefer navigating with my head rather than a map, I’d rattle the street names in the Loop off in succession: “Washington,—,—,Madison, Monroe, Adams, Jackson, Van Buren, Harrison,—,Polk, Taylor.”

The pauses were semi-deliberate—artifacts left from my days as a ten-year-old memorizing the presidents in a way that demands the same cadence every time.

But why did there have to be pauses at all? In this post, I set out to answer this question. Why are Chicago’s presidential streets all sorts of messed up? Why are some missing? Why are others out of order? Let’s find out!

Chicago’s Presidential Streets

Long before the Magnificent Mile, and even persisting to a degree today, the real heart of Chicago was south of the river.

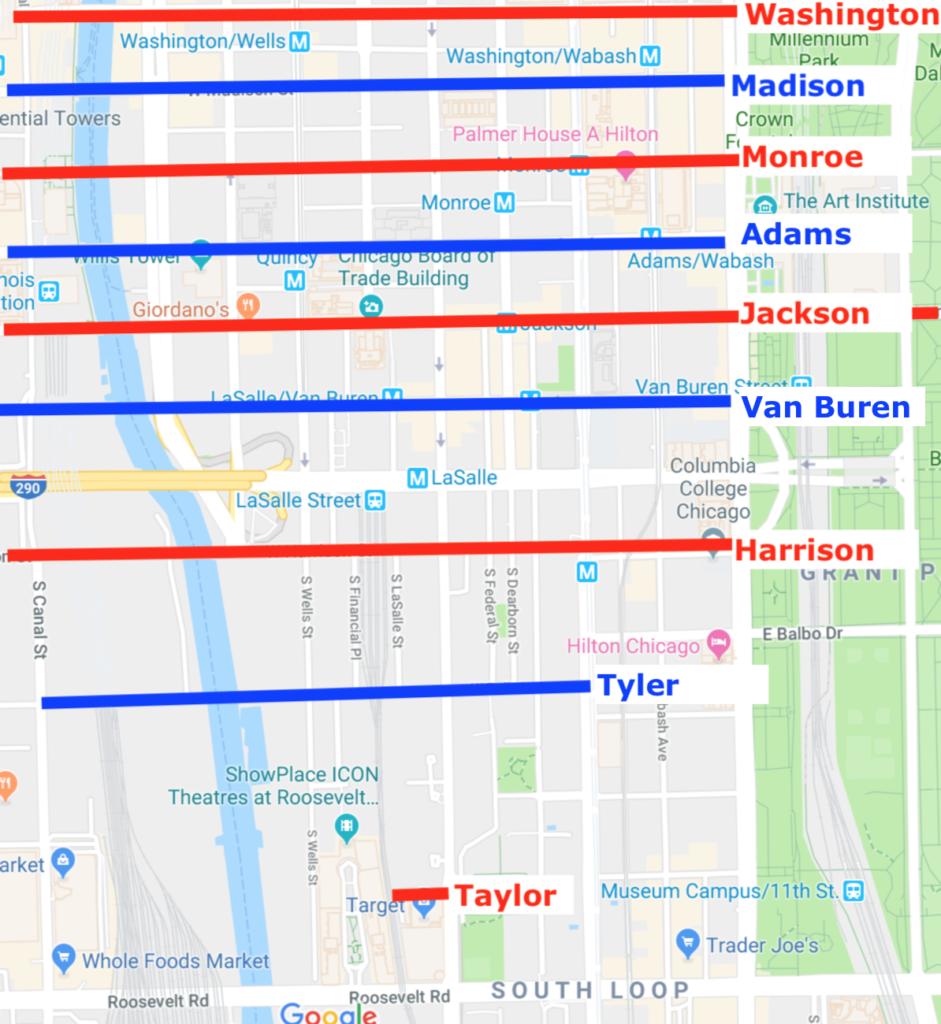

Most prominently in the Loop, but also continuing into the western part of the city are a series of streets named after presidents. In order, from north to south (learn more about Chicago’s grid system) there are:

- Washington

- Madison

- Monroe

- Adams

- Quincy

- Jackson

- Van Buren

- Harrison

- Polk

- Taylor

Fillmore exists, but makes no appearances east of the river. There are others in the city, like Roosevelt and Lincoln, but they were later-named and not exactly a part of this current discussion.

History buffs (or ten year olds who can rattle off the names of every president) will have little problem remembering the above order, as it is almost the order in which these presidents held office.

But why is it only almost? And why are some missing? Let’s sort all this out, starting with the easy one.

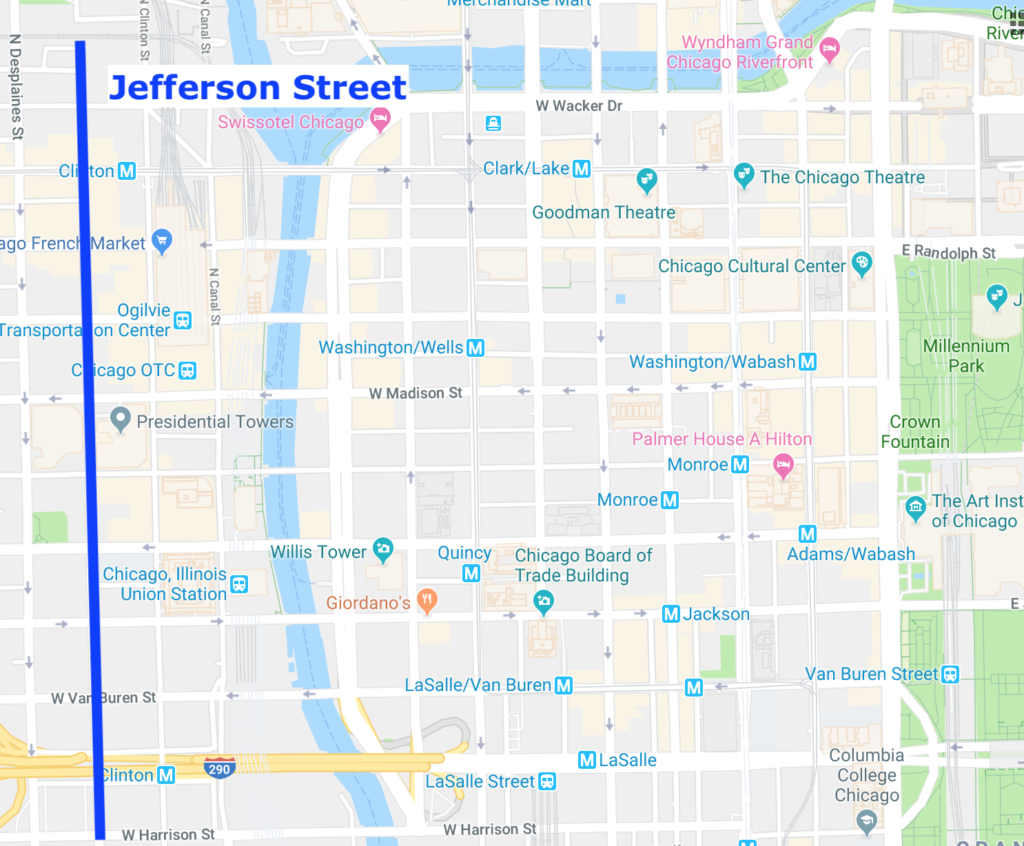

Where is Jefferson Street?

George Washington has Washington Street. There’s at least an Adams Street (more on this later). But there’s no Jefferson Street here…what gives?

This absence is easily explained—Jefferson Street does exist! Jefferson is a north / south street just west of downtown.

To understand how it wound up there, we have to go back in time a bit. Well, more than a bit…back to the beginning.

In 1830, James Thompson drew the first proposed map of the future Town of Chicago. For four main streets along the outside of the town (not always the edge of the map), Thompson went with:

- Kinzie Street in the north (named after Chicago’s first murderer)

- Dearborn Street in the east (named after Fort Dearborn)

- Washington Street in the south (named after the first president, George Washington

- Jefferson Street in the west (named after the third president, Thomas Jefferson)

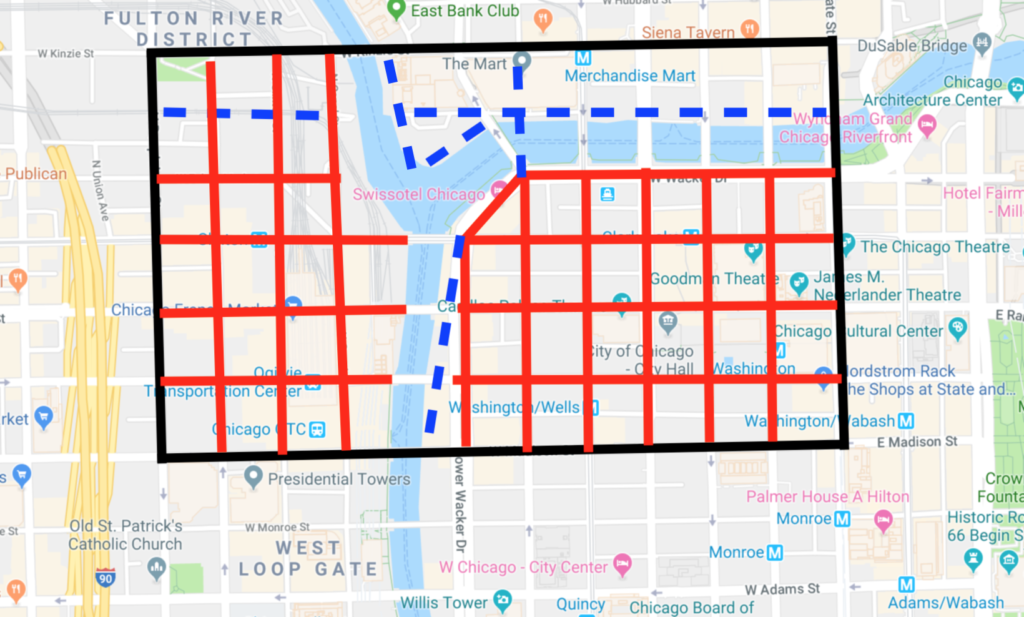

Thompson’s original plan has mostly survived all of Chicago’s history. In the below picture, the solid red and black lines are the surviving parts of the original plan. The dashed blue lines are parts of the original plan that no longer exist.

Nothing in the naming of the streets indicated any real pattern of naming after the presidents, it was just Washington and Jefferson.

Despite much searching and spending $30 for a Chicago Tribune Archives membership, I can’t find anything that definitively states why Thompson didn’t include an Adams Street.

The most reasonable explanation seems to come down to James Thompson’s downstate roots. Thompson came to Chicago from Kaskaskia, and many of his street names are similar to those of counties in downstate Illinois—Jefferson, Franklin, Randolph, and Clinton, for example.

While there is (and was) and Adams County, is located farther west, not really near Thompson’s hometown (and also allegedly named after John Quincy Adams).

Regardless, this seems less a snub of Adams and more just a chance to honor two important presidents with two major streets in Chicago. Though it does bring us to the next question…

Why is Adams Street out of order?

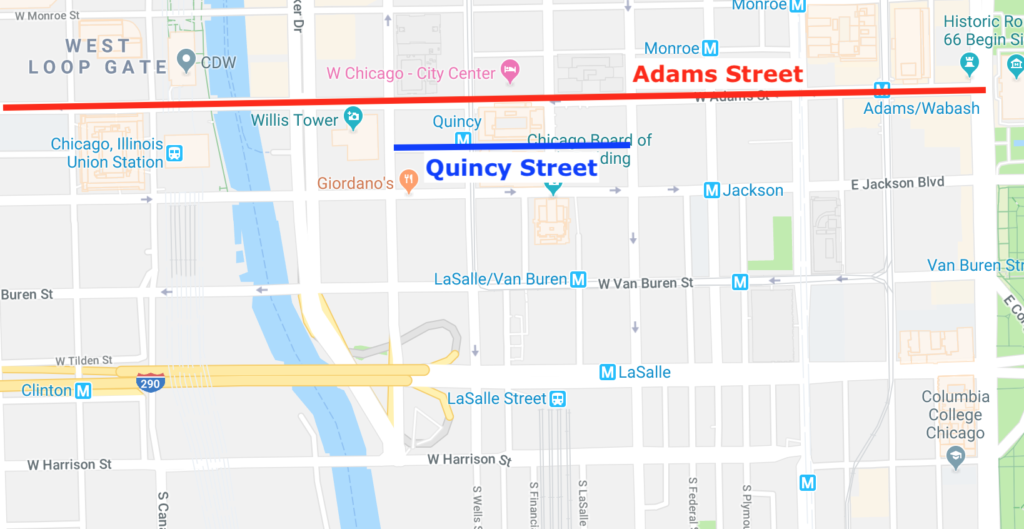

This one is a little more complicated. You have to start by recognizing that there are two problematic streets here.

First, Adams Street is south of Monroe Street and north of Jackson Street. Second, Quincy Street is a small street, between Adams and Jackson Street.

Who is Adams Street named after?

For the longest time, I just assumed Adams Street referred to John Quincy Adams, not John Adams (the elder), which keeps Monroe-Adams-Jackson in the proper order. Then I remembered / realized that Quincy actually exists as its own street and L train stop.

The stop is actually notable for being one of Chicago’s oldest and maintaining some of its old design.

So now…is Adams Street named after John Adams and out of order? Or does John Quincy Adams have two streets? And if so, why is John Adams missing?

A relatively recent explanation for this comes from Tom McNamee of the Chicago Sun-Times (and author of Streetwise Chicago). He addresses this in a 2007 column (paywalled).

What it comes down to is that I was right! Adams does seem to refer to John Quincy Adams. Well, sort of.

Cut it out. Who is Adams named after?

McNamee postulates that Adams Street was indeed named after John Quincy Adams, as its order clearly suggests. Given the politics of the time John Quincy Adams would also have had many fans in Chicago government.

The streets of Madison, Monroe, Adams, and Jackson were all added at the same time, in 1833 (here’s an 1836 map), further bolstering this idea.

Then where is John Adams’s street?

Well, McNamee thinks that while the younger Quincy Adams may have been a favorite of Chicago, the elder Adams was not, and so he was snubbed.

This is also a theory supported by former Municipal Judge William N Gemmill, who in 1923 wrote (paywall) that Chicago would not “stand for Old Silk Stocking Adams.”

This is a plausible, but unnecessary explanation that I can’t substantiate with any historical source.

Again, the streets of Madison, Monroe, Adams, and Jackson were all added together in 1833. Given that Washington and Jefferson were already established. It might have just made sense to go with the four recent Presidents after Jefferson.

So why is there a Quincy Street, too?

McNamee postulates that Chicagoans came to recognize Adams Street as referring to the elder John Adams, which is what led to John Quincy Adams needing a new street, Quincy.

This is supported by the 1923 Judge Gemmill piece, which claims that Adams Street was, by city resolution, rededicated to the elder John Adams. After all this, John Quincy Adams was given what little street could be found for him.

Any other theories?

Of course! Alfred Theodore Andreas in History of Chicago (1884) and Bernard Hollister in the Chicago Tribune (1980) (paywall) both claim that Quincy Adams was deliberately given the undersized street.

The idea here is that whether Adams Street was originally named for John Adams or whether he was later forgiven for whatever his faults, Adams Street is his.

Unforgivable, though, was John Quincy Adams being appointed by the House of Representatives following a split election in which he had fewer votes than Andrew Jackson. For that, he was given no street until a developer’s wife took pity on him.

This final theory sounds like a mix of fact and fiction. Purely by the fact that Madison, Monroe, Adams, and Jackson, were added at the same time, it seems certain that Adams originally referred to John Quincy Adams despite his unconventional path to the presidency.

Quincy Street, whether by the city’s action or that of a developer, seems like a last ditch effort to ensure the president was clearly honored rather than an insult at him from the get-go.

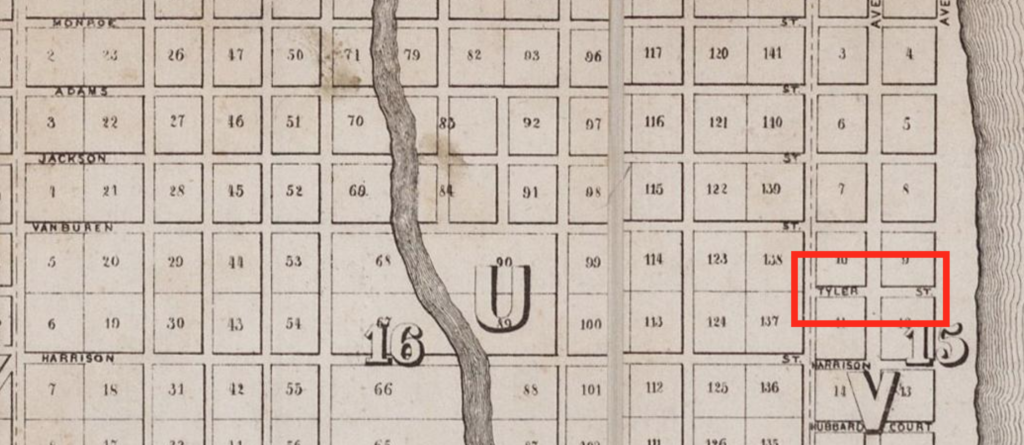

But where is Tyler Street?

So—you realized John Tyler is missing a street, too. Tyler Street should be between Harrison and Polk, but he isn’t. Indeed, this one seems to be another bit of snubbery—this time, in two parts…

Part 1. Tyler gets the short end of things.

It turns out Tyler Street did exist at least until 1871. You can see the street in older maps.

In that 1857 map, you can see Tyler Street twice. First, East Tyler Street runs between State and Michigan just north of Harrison, on what is today Ida B. Wells Drive, formerly Congress Parkway.

Second, West Tyler Street picks up somewhere around Halsted and runs farther west. This is, again, north of Harrison.

Already there’s a problem—Tyler was president after Harrison, and so should be south of him, at what is now Polk Street. Why is Tyler Street out of place?

No one seems to have a good answer for this, but you can piece together a pretty convincing puzzle.

Most sources suggest, and at least one 1849 map seems to confirm, that East Tyler—that measly one city block long strip—was the original Tyler Street.

Later (before 1857) probably just for simplicity, West Tyler Street was named accordingly. The West Tyler Street section is unnamed in the 1849 map.

So the question isn’t really why Tyler is out of order, it’s why he was so disregarded as to just be given this tiny street to begin with. The truth seems lost to history, but it isn’t hard to find possible reasons…

For starters, Tyler was never elected president. He assumed the presidency following the death of William Henry Harrison, for whom he was vice president.

Second, Tyler quickly ran into opposition within his own party, the Whigs, and was expelled from the party in 1841, early in his presidency. This upset many, including Chicago’s Whigs (one of the two major political parties in the city).

And so, Harrison gets his own street despite his short presidency. Tyler, who isn’t well-liked in Chicago and wasn’t elected president anyways, gets a sort of “footnote” where they can find space for him.

By 1857, cartographic simplicity trumped distaste for Tyler, and he was given West Tyler Street, as well. But we still haven’t answered–where is Tyler Street today?

Part 2. Tyler gets snubbed (again…probably).

By 1871, East Tyler Street was renamed Congress Street. By 1879, West Tyler Street got the same treatment, and Tyler Street was no more. Why?

The leading theory is that the name was changed because Tyler abandoned the Union for the Confederacy. This is an intuitive explanation, but the timeline doesn’t really hold up.

For one, we’ve already shown this second round of snubbing–renaming the street Congress–occurred in two parts. In fact, as early as 1857 it looks like East Tyler Street was already sharing the name “Congress Street.”

Alfred Theodore Andreas’ 1884 History of Chicago offers that East Tyler Street was renamed almost immediately after Tyler took office, when he was expelled from the Whig Party.

This makes enough sense. It’s not uncommon for streets to share names even after a formal renaming. 1857 is also prior to when Tyler became a public member of the Confederacy in 1861, suggesting the renaming of East Tyler Street was unrelated to that moment.

But what about West Tyler Street? Why was it renamed?

Without maps from every year, we can’t pin down the exact year West Tyler was renamed. However, the street still existed in 1872, a full 11 years after Tyler joined the Confederacy and 7 years following his death.

It was in August 1872 that the Special Committee of the Common Council on Street Nomenclature recommended that Tyler be completely renamed “Congress.”

A recap of a Council meeting (paywall) following those recommendations notes a “long discussion” about the change (which was one of dozens if not hundreds at issue), that resulted in Congress winning the day.

And so in 1872, Tyler Street ceased to be, and Congress Street (later Congress Parkway, the Eisenhower Expressway, and Ida B. Wells Drive) took its place.

But why make this change now, so many years after all of Tyler’s controversy? The answer is probably the Great Chicago Fire.

The Great Chicago Fire destroyed much of Chicago in late 1871. Although it barely touched West Tyler Street, the rebuilding and replanning that followed impacted far more than just the grounds that were directly impacted.

Prior to the fire, the city’s street names were an incredible hodgepodge. In March 1871—seven months before the fire—the Real Estate section of the Chicago Tribune (paywall) bemoaned the sad state of street nomenclature, citing examples of straight streets that had collected five different names.

It seems likely that while Tyler’s Confederate involvement may have given Chicago reason to rename his street, it was the replanning following the Great Chicago Fire that was the impetus.

Conclusions

Well, it’s been 2000 words, but hopefully you’ve learned a lot. Interestingly, we’ve maybe ignored the biggest mystery—why do Chicagoans care so much about street names to begin with?

Truthfully, I cannot say. We Chicagoans just have an attachment to the creative, I suppose. As “Property Holder” (a pen-name…probably) wrote to the Chicago Tribune in 1859 concerning the proposed name change of Clark Street to Broadway:

If there be a deficiency in the American character—it is a poverty of invention, a want of originality, not in mechanics, certainly—but in nomenclature, remarkable in so intelligent a people.

Property Holder, Chicago Tribune, September 6, 1859

I guess it’s always been a part of being a Chicagoan to be a bit uppity about your street names. Though we’re not always so clever at it. What did Mr. Holder want to rename Clark Street? Centralia. Consider me glad that never happened.